| UPDATE: Take action |

Madagascar est renommée pour sa richesse biologique. Située au large des côtes orientales du sud de l’Afrique et avec une superficie un peu plus étendue que celle de la Californie, l’île abrite une collection éclectique de plantes et d’animaux dont 80 pour cent ne sont rencontrés nulle part ailleurs dans le monde.

Madagascar héberge de véritables énigmes de l’évolution comme le fossa, un mammifère carnivore dont l’aspect tient à la fois du puma et du chien mais qui est affilié aux mangoustes ; l’indri qui est un lémurien de la taille d’un gros chat et qui émet un long cri chant plaintif non sans rappeler la baleine à bosse ; le propithèque, un autre lémurien, bien moins chanteur surtout lorsqu’il émet des cris d’alarme mais qui se déplace à terre comme seul pourrait le faire un danseur chevronné ; des caméléons et des géckos diurnes aux couleurs vives ; d’autres geckos nocturnes comme les uroplates au camouflage irréprochable qui leur permet de se fondre dans l’écorce des arbres sur lesquels ils passent le jour. On y rencontre aussi les baobabs qui semblent avoir été plantés à l’envers, la pervenche qui est employée dans le traitement des leucémies infantiles et de la maladie d’Hodgin ; et pour finir un écosystème complet avec une myriade de plantes épineuses mais sans cactus aucun. Et pour tout ça et bien d’autres éléments, les scientifiques ont fait de l’île – qualifiée de huitième continent – une priorité en matière de protection de la nature.

Indri lemur and Coquerel’s sifakas in Madagascar. Photos by Rhett A. Butler |

But Madagascar’s biological bounty has been under siege for nearly a year in the aftermath of a political crisis which saw its president chased into exile at gunpoint; a collapse in its civil service, including its park management system; and evaporation of donor funds which provide half the government’s annual budget. In the absence of governance, organized gangs ransacked the island’s biological treasures, including precious hardwoods and endangered lemurs from protected rainforests, and frightened away tourists, who provide a critical economic incentive for conservation. Now, as the coup leaders take an increasingly active role in the plunder as a means to finance an upcoming election they hope will legitimize their power grab, the question becomes whether Madagascar’s once highly regarded conservation system can be restored and maintained.

Baobab and deforested countryside in Madagascar. Photos by Rhett A. Butler |

Madagascar has been separated from mainland Africa for 160 million years and isolated from other land masses for at least 80 million. The result is an unusual mix of flora and fauna, most of which either predated separation or rafted to the island. These animals radiated to fill Madagascar’s many niches—ranging from dry deserts to mountain moorlands to tropical lowland rainforests—that result from its diverse topography and climate.

Humans were late arrivals to Madagascar, journeying across the Indian Ocean from what is now Indonesia (not Africa, despite its proximity) sometime in the past 2,000 years, making it one of the last major land masses to be colonized by man. Mankind has had profound impacts on the island’s flora and fauna. Humans hunted the largest species—including giant ground lemurs, hippos, and massive elephant birds—to extinction and drove landscape changes through persistent burning and the introduction of non-native species. Forests that once blanketed the eastern third of the island are today fragmented, degraded, and greatly reduced, while endemic spiny forests have been diminished by subsistence agriculture, cattle grazing, and charcoal production. The central highlands have mostly been cleared for pasture, rice paddies, and eucalyptus and pine plantations.

Environmental degradation in Madagascar is so extensive that it is now even visible from space. Astronauts have remarked that the red color of Madagascar’s rivers suggest the country is bleeding to death. In a sense, it is. The rivers are hemorrhaging topsoil. Poor as it may be, soil is the basis of agriculture and as one of the poorest nations on Earth, the people of Madagascar can ill afford this loss. Each year as much as a third of the country burns, primarily the result of fires set by farmers and cattle herders clearing land for subsistence agriculture or promoting the growth of new vegetation for animal fodder. Meanwhile industrial miners from developed countries are tearing away at some of Madagascar’s last remaining forest tracts for ore and mineral deposits.

Rosewood logging in Masoala National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site; burning near Andringitra National Park; and mining near Mantadia National Park. Photos by Rhett A. Butler |

Nevertheless, despite the carnage, the fragments of habitat that remain still support an astounding array of biodiversity. So rich in fact, that scientists are continuing to discover species. The number of lemurs in the definitive guide to lemurs—authored by Russell Mittermeier, the current president of Conservation International—has risen from 50 in 1994 to more than 100 today, while scientists last year announced a near doubling of the number of frog species known to occur on the island.

But over the past decade Madagascar has undergone a remarkable transition from the pariah of conservation to a model. While financial and technical support from foreign governments and international NGOs has been critical, local involvement and political commitment—in 2003 then President Marc Ravalomanana said he would set aside 10 percent of the country as parks—have been essential to slowing deforestation and protecting endangered wildlife on the ground. Madagascar’s park system mandates that half of park entrance fees flow back to local communities, ensuring that at least some benefits of ecotourism—two-thirds of visitors come to Madagascar for nature-related activities—reach people who may be otherwise disadvantaged by conservation initiatives. Indeed the emergence of ecotourism has been credited by some for making local people partners—rather than adversaries—in conservation.

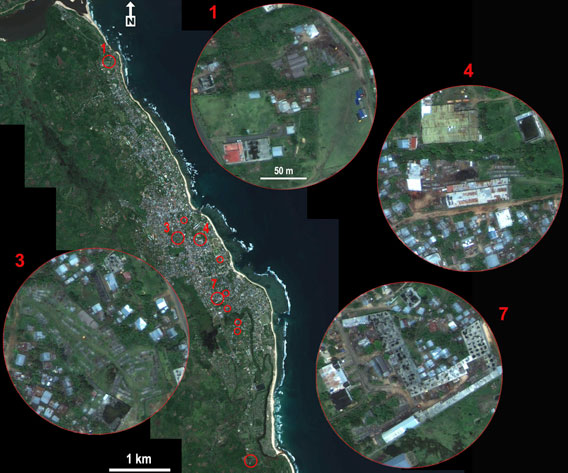

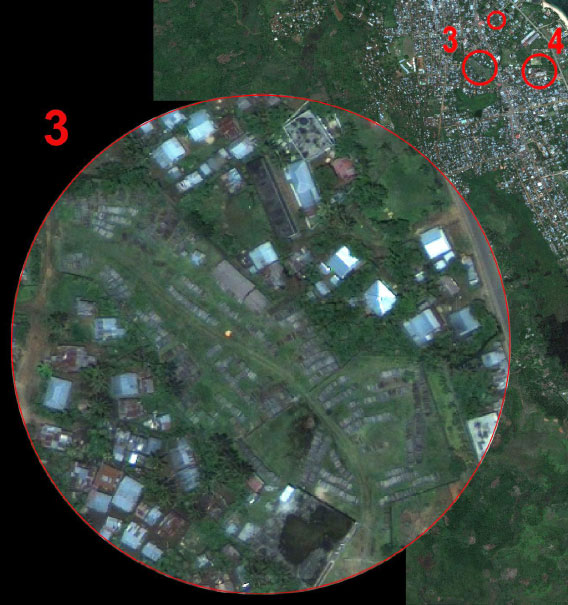

Rosewood logs awaiting pickup in Maroantsetra (top). Boat carrying rosewood in the Bay of Antongil (bottom).

Two ships belonging to Delmas, the Consistence and the Lea, were last year reportedly shipping rosewood out of Madagascar. The company now says it has quit the international rosewood shipping business but recent reports suggest it may be planning to ship rosewood between ports in Madagascar. Photos taken in Vohémar port, Madagascar. |

But these gains were all but erased by the political crisis in March 2009. Although the underlying drivers of the conflict remain in dispute, observers say the democratically elected Ranomalanava had become increasingly autocratic in his second term, shutting down opposition media outlets, using his political power to further his sprawling business interests, and signing controversial deals, including one that reportedly would have turned over half of Madagascar’s arable land to Daewoo, a South Korean conglomerate, for export-only crop production. After a series of demonstrations turned violent under questionable circumstances, a faction of army officers allied with Andry Rajoelina, the mayor of the capital city of Antananarivo, overthrew Ranomalanava, who fled to South Africa. In the aftermath of the coup, Madagascar’s reserves—especially in the northern part of the country—were ravaged by illegal loggers. Armed bands, financed by foreign timber traders and at times in collusion with local officials, went into Marojejy and Masoala national parks, harvesting valuable hardwoods including rosewood and ebonies. Without backing from the central government or support from international agencies that had been the source of nearly 90 percent of conservation funding, little could be done to stop the carnage.

Marojejy, a forested mountain that is among Madagascar’s most biodiverse parks with a dozen species of lemurs including the critically endangered Silky Sifaka, was the first to fall. Armed bands invaded the reserve, cutting trails, hunting wildlife, and extracting timber. Those who attempted to stand in their way were threatened—local radio reported that a park ranger from ANGAP, Madagascar’s protected areas agency, had both of his feet broken by representatives of timber barons in the northern town of Mananara. The chaos forced authorities to close Marojejy to tourists—its lifeblood—for the first time, effectively blocking outsiders from bearing witness so the plunder. Loggers soon moved into Masoala National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site that is considered one of the jewels of Madagascar’s protected areas. Logging was so intense in Masoala that the supply of cargo boats in the neighboring town of Maroantsetra was fully employed to haul rosewood out of the forest—none were available for conventional shipping. Other forest areas were also targeted. All told, logging affected 27,000-40,000 acres of protected rainforest, according to estimates from Lucienne Wilmé, Porter P. Lowry, Peter H. Raven of the Missouri Botanical Gardens, and Derek Schuurman of Rainbow Tours. More than $200 million worth of timber was cut. Much of it went to China to make wood products that will eventually be sold in Europe and the United States.

Rosewood logs.

|

What was particularly galling for conservationists about the episode was that logging was principally for commercial gain by well-connected traffickers, rather than subsistence harvesting by poor Malagasy. Erik Patel, a researcher from Cornell University who focuses on the Silky Sifaka in Marojejy, says that traders, not the common Malagasy villager, benefitted most from the illicit harvesting.

“Harvesting these extremely heavy and valuable hardwoods is a labor-intensive activity requiring coordination between local residents who manually cut the trees, but receive little profit, and a criminal network of exporters, domestic transporters, and corrupt officials who initiate the process and reap most of the enormous profits,” Patel said. “Local people benefit very little from rosewood logging. In most cases, rosewood logging is harmful to local people because of loss of tourism and violation of local taboos.”

At the same time that the northern rainforests were being pillaged for their timber, a disturbing new trade emerged: commercial bushmeat hunting of lemurs.

In August, Conservation International (CI), an NGO that has been particularly active in Madagascar, released photos showing piles of dead lemurs that had been confiscated from traders and restaurants in northern towns.

Loss of lemurs can have ecological effects in forests. According to Patricia Wright, lemurs appear to be the most important seed dispersers in Madagascar. Worryingly, Wright says that the “tastiest” lemur—as revealed by surveys of more than 2,000 individuals in local villages—is also one of the most important dispersers: the black-and-white-ruffed lemur.

These animals are the crowned lemur, Eulemur coronatus and the golden crowned sifaka, Propithecus tattersalli. Copyright: © Fanamby/photos by Joel Narivony |

“What is happening to the biodiversity of Madagascar is truly appalling, and the slaughter for these delightful, gentle, and unique animals is simply unacceptable,” said CI’s Russ Mittermeier in a statement released at the time. “And it is not for subsistence, but rather to serve what is certainly a ‘luxury’ market in restaurants of larger towns in the region. More than anything else, these poachers are killing the goose that laid the golden egg, wiping out the very animals that people most want to see, and undercutting the country and especially local communities by robbing them of future ecotourism revenue.”

Until the coup, ecotourism had been an economic bright spot for Madagascar. Lured by its spectacular landscapes, unmatched biodiversity, and cultural richness, tourist arrivals had been growing, reaching $390 million in 2008. But the trend shifted abruptly with the political turmoil and violence, with rich-world governments advising their citizens to avoid Madagascar. Tourist arrivals dropped sharply during the crisis—50 to 60 percent island-wide for the year by some estimates. International carriers cut flight service but workers employed directly in the tourism industry were particularly affected. During a September visit to Perinet Special Reserve, the home of the famous singing Indri lemur, nature guides idled in front of lodges, waiting for tourists, and loitered along the road to a mining area, hoping to pick up work as day laborers. The lucky ones had managed months ago to line up temporary work at a $3.8 billion nickel mine run by Sherritt, a Canadian mining firm. The project will eventually send millions of tons of mining sluice to the coastal port of Tamatave via an 85-mile-long pipeline that runs between to two protected areas. At 400,000 ariary ($200) per month, it is the best job in town.

|

The decline in tourism has been felt widely in Madagascar, but some have suffered more than others. Some operators in the north said business is down by as much as 80 percent relative to last year. In Ranomafana, arguably Madagascar’s best-managed park, tourist arrivals are down by more than 40 percent, according to Patricia Wright, executive director of the Institute for the Conservation of Tropical Environments (ICTE) at Stony Brook University and a leading force in conservation in Madagascar over the past 20 years. Wright has tracked tourism in Ranomafana over the past decade and says that during Madagascar’s last political crisis in 2002, tourist arrivals in Ranomafana fell from 16,000 to less than 3,000, a drop of more than 80 percent. Last year 24,000 tourists visited the park, generating $1.72 million in revenue.

Local officials in Ranomafana confirm the crisis has adversely affected the town and the park.

“Tourism in Ranomafana National Park has decreased by 45 to 46 percent compared to last year and overall for Fianar province tourism has decreased by 70 percent,” said Mamy Rakotoarijaona, manager of the Ranomafana National Park, via a translator. “Ranomafana National Park and Isalo National Park [another popular park] have been faring better then other national parks, but still hurting. This makes a big impact on the economics of the villages as 50 percent of the park entrance fees are used for village conservation and development projects.”

“Tourist guides and local shopkeepers are suffering from the lack of tourists,” added Leon Razanakoto, the mayor of Ranomafana. “We are hoping that tourism will come back again next year with the elections in place.”

The standstill has also hit downstream businesses indirectly linked with tourism. Farmers are selling less rice and zebu, shopkeepers are selling fewer bottles of Eau Vive, the ubiquitous drinking water most often consumed by tourists, and bundles of fresh vanilla beans, a popular souvenir.

The downturn has made some Malagasy aware of just how important visitors—two-thirds of whom come to Madagascar to see its wildlife—are to their well-being.

“Many people didn’t believe that bringing vazaha [the local term for foreigners] to the forest helped them,” said Claudio, a nature guide based in Maroantsetra, a town that is the jumping-off point for Masoala National Park. “But the crisis has shown them that tourism does bring benefits. Everyone is feeling it now—the political crisis has become an economic crisis.”

Verreaux’s sifaka in southern Madagascar

|

For conservation, the fall in tourist revenue has been exacerbated by the loss of donor support. USAID, a major source of finance for conservation projects, and other organizations have frozen funding, while the Peace Corps has pulled its volunteers out of the country. NGOs have been pleading to governments to restore aid. Zurich Zoo, which backs a conservation project in Masoala, has gathered thousands of signatures in a petition drive, calling for restoration of law enforcement and resumption of aid. There are worries that the suspension of projects has eroded confidence among local communities that conservationists are committed to Madagascar for the long haul.

While the situation improved in the second half of 2009 with gendarmerie moving into some critical areas and a series of arrests of illegal loggers (who were subsequently released), it has worsened since the end of the year. In mid-December it became clear the shipments of illegally logged timber would resume after a temporary moratorium. A major shipment—worth an estimated $20-80 million—was planned for December 21 until a global campaign led by Ecological Internet, an Internet-based activist group, forced the French shipping company, Delmas, to leave port without any timber. A representative from Delmas said afterwards that transporting the timber wasn’t worth the damage to its reputation.

But the reprieve didn’t last long. On December 31, Rajoelina’s transitional authority authorized the export of rosewood, signaling to loggers that they could now cash in on their efforts. Immediately following the decree, reports on the ground indicated an upswing in logging activity in Masoala and Makira National Parks. In the midst of a cash-crunch, Rajoelina’s government was apparently selling out Madagascar’s forests to finance an election that it hoped would validate its seizure of power. To ensure this outcome, Rajoelina’s forces cracked down on the opposition, tear-gassing protesters, arresting journalists, and shelving scheduled parliamentary elections. His actions, which have also included rejecting a series of power-sharing agreements, have provoked strong condemnation from the outside world. The United States terminated trade preferences with the country and, together with other countries, is said to be weighing sanctions. Donor governments have said that aid is unlikely to resume until democratic rule returns to Madagascar.

In the meantime, the pillage of the island’s parks is expected to continue.

|

TAKE ACTION: Forests.org has relaunched a campaign parties partaking in, and facilitating the destruction of Madagascar’s rainforests. |

|